Greetings, medico-historico aficionados, and welcome to the latest installment of CPP Curiosities, our semi-regular foray into weird and interesting chapters in medical history. Past articles have addressed treating syphilis by infecting patients with malaria, a fake Persian mummy who may have been a real murder victim, and graverobbing on top of graverobbing.

The leaves are changing, people are gearing up for Halloween and the subsequent two-month mad dash to the holiday season (only 75 more shopping days until Christmas, everyone!). We are in the midst of an annual American tradition: Major League Baseball’s postseason. The road to the World Series is heating up, and even though our hometown Philadelphia Phillies have long since been eliminated from playoff contention (sometime around the July All-Star break if my memory serves) there are many ball fans of more successful teams who are excited. In the spirit of the postseason, I thought we’d dive into a topic that marries both baseball and weird medical history. With that in mind, read on to learn about possible life after death, the science (or lack thereof) of human preservation, and one of the greatest hitters in baseball history.

Cryonics

Some of you may have heard of cryogenics. Also known as cryonics, cryogenesis, or cryopreservation, it is the practice of having all or part of a person’s body stored at sub-zero temperatures. The ultimate goal, in theory, is they can eventually be thawed and revived. Its medical applications generally involve freezing a patient with an incurable disease or traumatic injury in the hopes that future medical/scientific advances can heal them or that technology advances enough to allow human consciousness to be transferred from the body to another vessel (i.e. preserved and stored electronically). Conceptually, the idea of placing a person in suspended animation, by freezing or otherwise, has a long history in fiction, from Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet to Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, to Philip K. Dick’s novel Ubik to Matt Groening’s Futurama. However, modern attempts to bring the concept off the page and screen date and into the real world back to the 1950s. While academic articles circulated in the 1940s and 1950s, the first work on the subject directed at a mass audience was Robert Ettinger’s 1964 book The Prospect of Immortality, a treatise on the scientific feasibility of human cryopreservation. His work led to public interest in the practice and several entrepreneurial enterprises. The first attempt to preserve a body via freezing occurred in April 1966, when Cryocare Corporation froze a recently-deceased elderly woman from California. The following year, on January 12, 1967, technicians froze deceased psychology professor James Bedford (cryonics enthusiasts celebrate January 12 as “Bedford Day”).

As described in a pro-cryonics journal, advocates for the scientific feasibility of cryonics cite four principles: (1) metabolic function is arrested in bodies preserved under sufficiently low temperatures, thus allowing them to be effectively preserved indefinitely; (2) the use of specialized chemicals can reduce or prevent the risk of damage to the body when frozen; (3) biological death, as opposed to legal death, is a process not an event; and (4) future scientific/technical methods could potentially allow cryogenically preserved people to be revived.

In the case of modern cryopreservation, after physicians establish time-of-death, representatives from a cryopreservation group or one of its subsidiaries preserve the body for transit to a cryonics facility. The body is placed in an ice water bath and attached to devices designed to maintain blood flow and respiration (to minimize deterioration) until the body reaches its destination. When it arrives, blood is replaced with a specialized solution designed to protect the body from damage while freezing. If only the patient’s head is being preserved (described in the business as neurocryopreservation or simply “neuro”), technicians remove it from the body. The body or head is then placed into a storage container called a “dewar” and frozen with liquid nitrogen, remaining in a frozen state until science catches up with science fiction (More on the procedure here).

A Dewar used in cryopreservation

Photo courtesy of Alcor Life Extension Foundation

It may not surprise you to know there are some key challenges to cryopreservation. For one thing, its efficacy is difficult to test. There’s currently no way to revive a cryopreserved patient and it’s difficult (and illegal) to subject human test subjects to a procedure that effectively has a 100% fatality rate. A patient cannot legally be preserved until after they’re dead. Alcor Life Extension Foundation, one of the more prominent cryonics services, concedes cryopreservation on a living subject is legally considered murder or suicide depending on who initiates it. This leaves cryotechnicians with the trouble of curing death in addition to whatever ailment brought about the patient’s end. As a result, cryonics leaves a lot of the work up to future scientists to help finish the job for them. Failure rates and deterioration of specimens are also issues. Modern cryonics facilities claim to make every effort to minimize the amount of deterioration due to extreme temperatures; however, there is a risk. According to a report from Alcor, with the exception of Bedford, every other cryonics patient preserved before 1974 eventually suffered some manner of failure. The general scientific consensus is, while it’s certainly possible to preserve a body under extremely low temperatures for a long period of time, the odds of revival are so low as to invalidate the endeavor. Advocates, meanwhile, retort that even an astronomically small chance of transcending death is better than no chance at all.

![An image from the animated series Futurama. Shows a sign reading "Applied Cryogenics: No Power Failures Since 1997 [the seven in 1997 is taped over another number]"](https://mutteredu.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/applied_cryogenics_2.jpg?w=640&h=480)

Image Source: 20th Century Fox. Used under fair use.

Another challenge for cryonics enthusiasts: the process is extremely expensive. While companies like Alcor assure that much of the cost can be covered through life insurance, aspiring patients need to be prepared pay

between $80,000 and $220,000 (depending on whether they opt for “neuro” or “whole body” plus additional fees) upon the event of their death. According to Alcor, the cost covers the initial procedure, general storage and maintenance as well as a trust patients can access after their reanimation. (A small price to pay for immortality?)

The Strange Case of Ted Williams

Often when one brings up the subject, as was my experience, people often mention Walt Disney. This refers to a persistent (and discredited) myth that the founder of the now-monolithic company responsible for most of our youthful amusement had himself cryogenically frozen following his death in 1966. However, perhaps the most famous person who was actually cryogenically frozen was legendary baseball player Ted Williams.

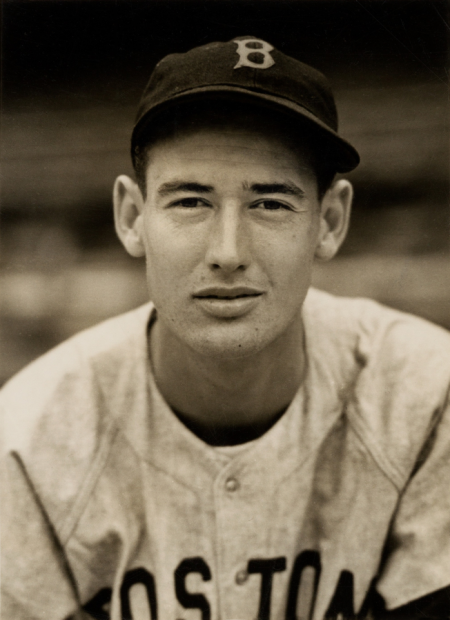

Theodore Samuel “Ted” Williams (1908-2002) was a longtime outfielder for the Boston Red Sox. During his nineteen-year career, 1939 to 1960 with a brief hiatus in the 1940s to serve in World War II, he was a two-time American League (AL) MVP (Most Valuable Player), a six-time AL batting champion (highest batting average in the league for the season), and an AL All-Star in every season he played. When he retired in 1960, he ranked in the top ten all time in career home runs, batting average, slugging percentage, and RBI (runs batted in). Williams still holds the record for the highest on-base percentage in major league history (full stats). He was a first-ballot Hall of Famer in 1966, and he ranks among one of the greatest baseball players of all time.

Ted Williams in 1939 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Ted Williams died of congestive heart failure on July 5, 2002. Following his death, representatives from Alcor shipped Williams’ body from Florida to their facilities in Scottsdale, AZ. There, technicians separated his head from his body, placing the head and torso in separate Dewars.

His passing and subsequent preservation triggered a bitter legal battle among Williams’ three children over the ultimate fate of his remains. His oldest daughter, Bobby-Joe Ferrell along with several other relatives and family friends, argued Ted Williams’ final wishes were to be cremated. However John Henry and Claudia Williams, his son and youngest daughter, respectively, argued Williams had had a change of heart before his death, opting instead for cryopreservation. John Henry developed an interest in cryonics in the late nineties and reached an agreement with Alcor to have his remains along with his father and sisters’ be preserved and stored at Alcor following their deaths. A legal battle ensued: John Henry asserted his power of attorney over his fathers’ affairs, while Bobby-Joe accused John Henry and Claudia of falsifying a consent form from their father. Eventually, Bobby-Joe allowed her brother and sister to keep Williams frozen on the condition that they not attempt to sell her father’s DNA (perhaps so he could be cloned and attempt to re-break his old hitting records). She also agreed to not publicly discuss Williams’ cryopreservation. In exchange, John-Henry and Claudia agreed to pay Bobby-Joe her share of her inheritance.

There was no shortage of press attention for the salacious details of Williams’ afterlife. It didn’t take long for accounts to circulate that Alcor was mishandling Williams remains. In July 2002, reports came out that his head had to be refrozen after cracks began to appear. In 2009, Larry Johnson, Alcor’s former chief operating officer, published a tell-all book about the company’s most famous tenant; among the more shocking accusations he levied against Alcor was that technicians reportedly hit Williams’s head multiple times with a wrench to jar it loose from a pedestal made out of a tuna can. (It hasn’t been the only scandal surrounding the company. In 1988 rumors circulated former Alcor executive Saul Kent poisoned his mother before cryopreserving her head). Moreover, a series of misfortunes brought his cryogenically-frozen future into jeopardy. An August 2003 article in Sports Illustrated reported John Henry still owed Alcor $110,000; according to Johnson, Alcor executives joked they would send Williams’s thawed body back to his son in a cardboard box.

It isn’t clear how matters were resolved between John Henry and Alcor; when John Henry died of leukemia in 2004, his remains were brought to Alcor for cryopreservation and his father remains there in frozen stasis to this day.

If this grisly story hasn’t satiated your need for accounts of preservation (or lack thereof) of notable figures, you can check out my previous article on the preservation of Vladimir Lenin’s body.

Until next time, catch you on the strange side!

![An image from the animated series Futurama. Shows a sign reading "Applied Cryogenics: No Power Failures Since 1997 [the seven in 1997 is taped over another number]"](https://mutteredu.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/applied_cryogenics_2.jpg?w=640&h=480)