By Phoebe Warren, Center for Education Intern

The Center for Education celebrated Black History Month and the 2022 theme of health and wellness through a series of Instagram posts honoring the herbal medicinal traditions of enslaved African and African American healers. We’re publishing the content of the entire series here. Many of the plants we feature can be found during the warmer months in the Benjamin Rush Medicinal Plant Garden here at the College. Please visit us if you’d like to see these plants in person!

These posts touch on several themes including respiratory illness, spiritual empowerment, the sources of enslaved people’s medicinal knowledge, and reproductive health. All these themes demonstrate the resilience and wisdom of Africans and African Americans who used the medicinal powers of plants to do what they could to support their health and wellbeing in the oppressive, dangerous, and dehumanizing realities of slavery.

If you are interested in learning more about African American healers and plant-based remedies, Herbert Covey’s book African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments (2007) is an excellent starting point. The Federal Writers’ Project Slave Narratives, available online through the Library of Congress, is one of the most extensive series of interviews of formerly enslaved African Americans. These interviews were conducted by writers in the late 1930s with funding from the Works Progress Administration. The narratives are complicated historical sources. For example, there was often a cultural and racial disconnect between the writers and the people interviewed. Nevertheless, the project is one of the most extensive efforts to document the experiences and memories of formerly enslaved people.

Disclaimer: It’s important to note that some of the plants featured below are toxic and are not recommended for use. Please consult a medical professional before using any herbal supplement.

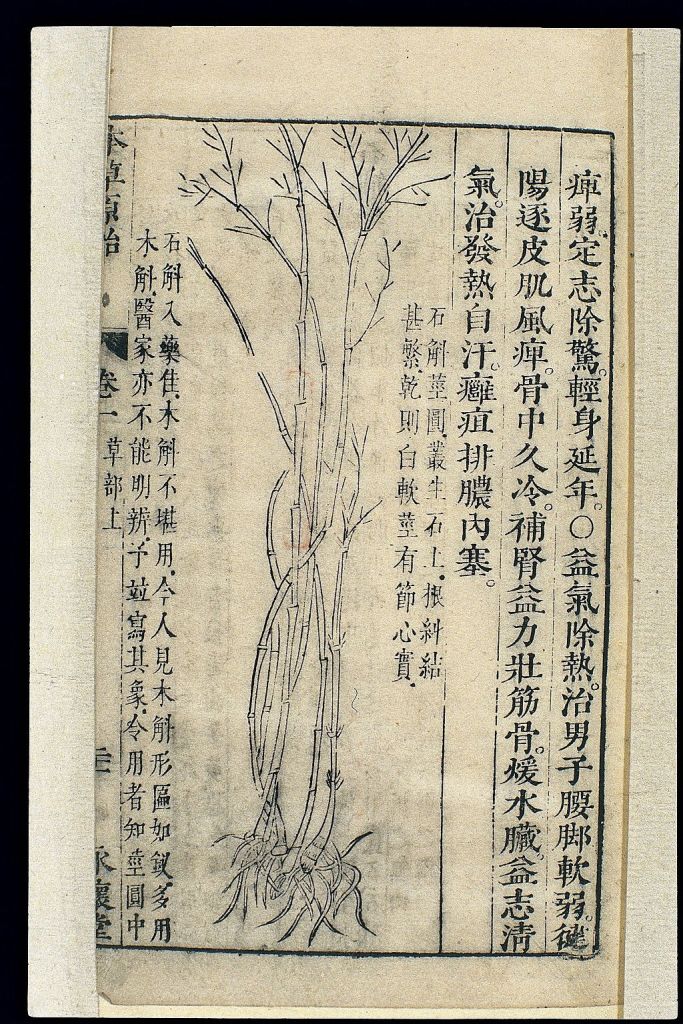

Knowledge of the curative powers of plants was a way for Africans and African Americans to survive and care for themselves and their loved ones. Plant knowledge and ritual practices around health and healing were passed down through generations.

This vessel, found on the Curriboo Plantation in South Carolina, was made by hand by enslaved people and was used for preparing food and medicines. Similar handmade pottery has been found throughout the American South. Some are marked with symbols similar to cosmograms, sacred symbols found in West and Central African spiritual traditions.

Horehound – Marrubium Vulgare

Respiratory diseases like pulmonary tuberculosis, whooping cough, and bronchitis affected the health of enslaved Africans and African Americans. In Federal Writers’ Project interviews in the 1930s, formerly enslaved people remembered using horehound to soothe sore throats and coughs. Sally Murphy of Alabama recalled, “When any of us got sick, we was give horehound tea and rock candy.” Horehound is native to North Africa, Europe, and Central Asia, and is part of the mint family. Horehound contains chemical compounds that act as expectorants to loosen and clear mucus from the airway.

Ferula species

Ferula species (possibly Ferula foetida), which formerly enslaved people referred to as “asafetida,” were also used to treat respiratory illness. These plants are members of the carrot family. Today, the term asafetida usually refers to dried latex prepared from the plant’s roots. Ferula species have a strong odor and are also known as “stinking gum” or “Devil’s dung.” Africans and African Americans used asafetida as a preventative against respiratory diseases. It was thought that breathing in the plant’s odors would kill disease-causing material. Lizzie Norfleet described her experiences under slavery in an interview with the Federal Writers’ Project: “Every child wore an asafetida bag round the neck to keep from ketching diseases.”

Elderberry or Elder · Sambucus sp. (Sambucus canadensis, Sambucus nigra)

Many Africans and African Americans believed in the power of time-honored remedies and trusted healers to cure illnesses. By growing and foraging for medicinal herbs, enslaved people were empowered to heal themselves and their loved ones. However, if those they cared for did not recover, enslaved healers were often blamed by white overseers and enslavers. Laws enacted by the Virginia legislature as early as 1748 determined that enslaved people administering medicines without approval by their enslaver was an act punishable by death. Sacred practices for health and healing, sometimes conducted in secret, were a means of survival for Africans and African Americans enduring the cruelties of enslavement.

In Federal Writers’ Project interviews, formerly enslaved African Americans recalled using elderberry, also called elder, as a powerful preventative and remedy. Harriet Collins of Texas remembered that elder was placed around infant’s necks to prevent discomfort when teething. Rachel Goings of Missouri described a remedy for sores: “I’d a took elder leaves en boiled em to make a tea—den I’d poured dat in de sore and it ud got well.”

Coneflower or Sampson root · Echinacea sp.

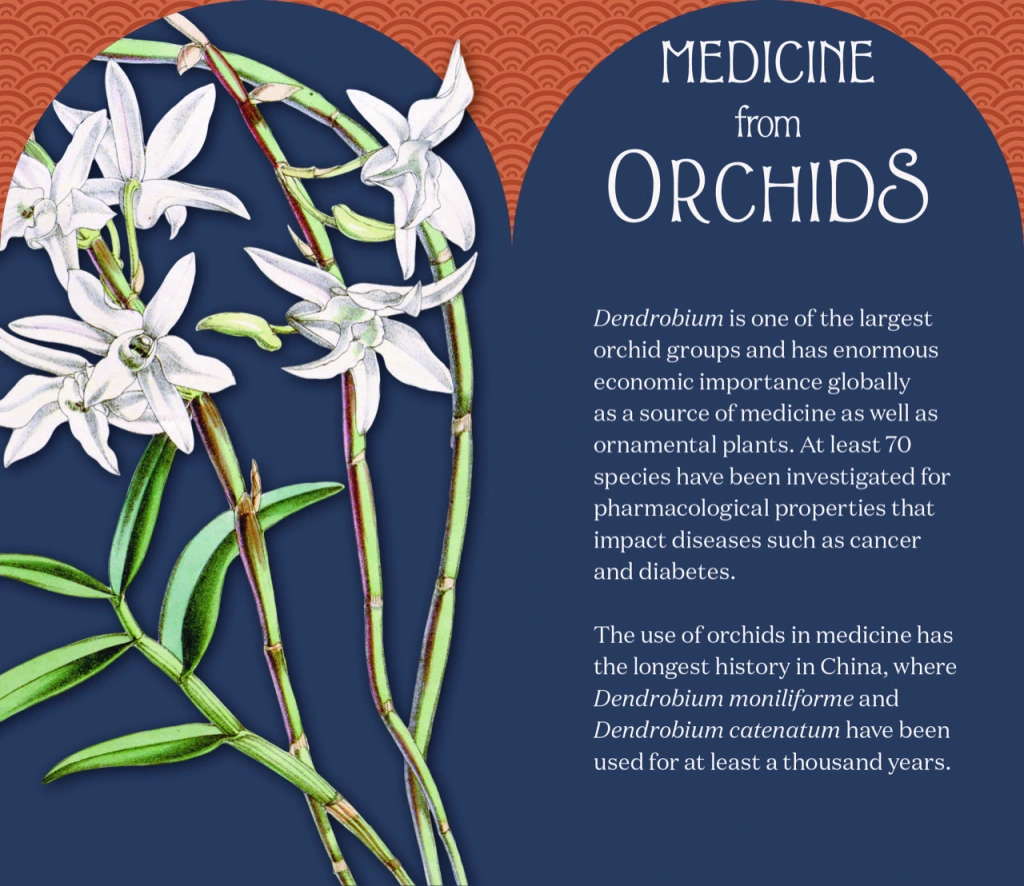

Enslaved Africans and African Americans learned about local medicinal plants from Indigenous healers. Native Americans had and continue to have an intimate knowledge of local plants. Native Americans were sometimes enslaved alongside Africans, and some Native American towns sheltered people seeking freedom from slavery. Knowledge about medicinal plants was likely shared in these contexts.

Coneflower is native to North America. Native Americans used the plant to treat gastrointestinal issues, fevers, sore throats, toothaches, and burns. In interviews with the Federal Writers’ Project, formerly enslaved African Americans called this plant Sampson root. Phil Town of Georgia remembered using a Sampson root tea to cure cramps. Pierce Harper of Texas and Fannie Moore of North Carolina both used the plant to treat stomach pain.

Okra · Abelmoschus esculentus

African people forced into enslavement had a rich knowledge of the medicinal powers of plants. The indigenous plants of the Caribbean and American South were very different from those of West and Central Africa. But some African plant species were brought to the Americas as a result of the transatlantic slave trade. Some of the captured African people who survived this unimaginable journey wore strings of plant seeds, such as wild licorice. Enslavers lined the holds of slave ships with African grasses. Crops brought from Africa like okra, yams, and black-eyed peas were staple foods for enslaved Africans and African Americans.

Okra was also used for medicinal purposes. Katie Arbery, a formerly enslaved African American who was interviewed through the Federal Writers’ Project, described the healing power of okra. Arbery remembered a time when she was so sick that, “They give me up to die once.” After trying different medicines with no success, her doctor “fed me for three weeks steady on okra soup cooked with chicken…Then I commenced gettin’ better and here I am.”

Cotton root · Gossypium herbaceum

Many enslaved African and African American women were sources of medicinal knowledge, and many served as midwives and healers. Using plant-based remedies and knowledge gained from experience, enslaved midwives delivered babies and did what they could to alleviate complications with pregnancy and childbirth. Enslaved women used different plants as contraceptives, abortifacients, and to regulate menstruation, induce labor, and ease labor pains.

Enslaved women’s reproductive health was threatened by inhumane conditions, malnutrition, rape, and violence. The plantation system pressured enslaved women to have as many children as possible. In interviews with the Federal Writers’ Project, formerly enslaved African Americans described that in secret, enslaved women used the root of the cotton plant to prevent pregnancy. When 19th-century white physicians and enslavers became aware of this practice, it was seen as a threat. Although enslaved women were denied the right to have control over their reproductive lives, they resisted by using plant-based medicines and other methods to assert agency over whether and when they had children.

Sage · Salvia officinalis

The medicinal practices of enslaved Africans and African Americans have been systematically left out of the historical record. In the 18th and 19th centuries, white legislatures passed laws limiting enslaved people’s access to plants and preventing them from practicing medicine. Enslaved people were often prevented from learning how to read or write. The institution of slavery separated families from one another and purposefully disrupted the passing down of generational knowledge.

Today, thanks to the work of researchers, community leaders, and libraries, these histories are being told. Please look out for and share these stories, and support Black healers, botanists, and gardeners in your community! It’s our hope that this series will encourage us to look differently at the plants we encounter, including herbs like sage. Sage was used by enslaved people as a cure for fever, chills, or, as Mrs. Mary Kincheon Edwards of Texas remembered, “Some people would use it fo’ almost anything.”

Bibliography

Aćimović, Milica et al. “Marrubium vulgare L.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Overview.” Molecules 25, no. 12. June 24, 2020.

Andreae, Christine. “Slave Medicine.” Jefferson Library at Monticello.

Covey, Herbert C. African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments. Lexington Books, 2007.

Eisnach, Dwight, and Herbert C. Covey. “Slave Gardens in the Antebellum South: The Resolve of a Tormented People.” The Southern Quarterly 57, no. 1 (2019): 11-23.

Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 2, Arkansas, Part 1, Abbott-Byrd. November-December, 1936.

Ferguson, Leland & Kelly Goldberg (2019) “From the Earth: Spirituality, Medicine Vessels, and Consecrated Bowls as Responses to Slavery in the South Carolina Lowcountry.” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage, 8:3 (173-201). DOI: 10.1080/21619441.2019.1690843

Fett, Sharla. Working Cures: Healing, Health, and Power on Southern Slave Plantations. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. Pg. 63-65.

Native American Ethnobotany: A database of plants used as drugs, foods, dyes, fibers, and more, by Native Peoples of North America.

Owens, Deirdre Cooper. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology, University of Georgia Press, 2017. Pg. 42-72.