Welcome back, fellow historio-medico enthusiasts, to the latest installment of CEPI Curiosities. Past articles have addressed such curious topics as historic forensics, the mental state of Presidential candidates, and graverobbing after graverobbing after graverobbing. This time around, we’re dealing with another important topic: medical experiments on prison inmates.

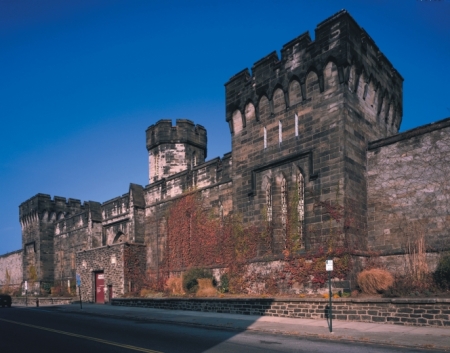

Holmesburg opened in 1896 as a prison for the City of Philadelphia. A massive structure with ten cellblocks, the prison’s radial design was based on that of Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary. Holmesburg still stands today; however, it has not served as an active prison since 1995 and is largely a ruin. Between 1951 and 1974, the facility was the site of a series of medical testing programs that would later become the subject of intense controversy, as the medical tests involved experiments conducted upon the inmates themselves.

Enter Albert Kligman. In 1951, Dr. Kligman was a professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. He went on to be a leader in his field; he later served as the President of the Philadelphia Dermatological Society (1975-76) and the President for the Society for Investigative Dermatology (1977-78) and earned a Distinguished Achievement Medal for his contributions to dermatology from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (where he was also a Fellow) in 2003. He is also the creator of Retin-A, also known as tretinoin, a topical medicine of his own design now used as acne cream and anti-aging treatment. According to one account, the accomplished dermatologist came to Holmesburg in 1951 to help treat an outbreak of athlete’s foot among the inmates.

Albert Kligman in 1955. Image Source: National Library of Medicine; used under Fair Use

In his eyes, he came across something much more valuable in the Northeast Philadelphia correctional facility than itchy, burning feet: a treasure trove of potential test subjects. “All I saw before me were acres of skin,” Kligman later told a Philadelphia newspaper reporter, “It was like a farmer seeing a field for the first time.” Kligman certainly found fertile soil in the Holmesburg inmates, a predominantly poor, African American population. Kligman and his associates convinced the prisoners to opt into medical experiments in exchange for small stipends. The facilitators of the experiments reassured them there were no hazardous materials or risk of long-term effects and hundreds of inmates served as test subjects over the next twenty years.

Under Kligman’s supervision, tests focused on the effects of various additives on human skin. These included medicated skin creams for treating various ailments, such as ringworm, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster and bacteria staphylococcus aureus (Staph infection). Other tests exposed prisoners to to biological agents, such as dioxin (a toxic chemical used in herbicides and an ingredient in Agent Orange) and hallucinatory drugs (as part of a federal government program known as “Project Often”). Inmates involved in the experiments could be easily identified by patchwork patterns of tape on their backs and arms demarcating the numerous skin tests. The tests continued until 1974, when public outcry prompted the researchers to bring the programs to an end.

Popular accounts during the course of the program were fairly favorable; the use of prisoners for medical testing was a common practice (see also the malaria experiments on inmates at the Statesville Penitentiary in Illinois as a contemporary example) at the time. However, opinion turned against the Holmesburg experiments following public outcry over the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” Conducted at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama from 1931 to 1972, the study examined rural sharecroppers from the surrounding area in an experiment on the long-term effects of untreated syphilis on the human body (the effects of which are illustrated by this skull and this wax model from the Mütter Museum collection). The syphilitic patients, predominantly poor African American sharecroppers, were not made aware they suffered from the disease (rather, their condition was described as “bad blood”); all the while scientists monitored the progress of the disease. The program continued even after the development of antibiotics that could combat the disease and did not cease until 1972, when a public backlash ended the program. A lawsuit ensued and the Institute and the federal government reached an out-of-court settlement in 1974 for $10 million. The Tuskegee experiments had long-term consequences, prompting local mistrust in healthcare professionals (in fact, fears over Tuskegee may have played a role in the progression of a tuberculosis outbreak in the region in January 2016).

Skull with Syphilitic Necrosis, Mütter Museum, 1161.07

Calls for similar compensation for the Holmesburg inmates persisted for many years after the experiments ceased. During the early 1980s, several inmates filed suit against the agencies involved in the experiments, including the City of Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania, Dow Chemical, and Kligman himself. One former test subject–Leodus Jones–received a $40,000 settlement from the City of Philadelphia in 1984.

As in the Tuskegee case, the argument over the experiments conducted at Holmesburg revolved around informed consent and whether the volunteers were made properly aware of the risks involved in participating. Informed consent is an important issue, especially when it comes to testing experimental drugs, and debates over what it means and who can give consent continue to this day. In the case of the Holmesburg inmates, Kligman asserted his experiments followed the proper procedures and emphasized the medical benefits yielded from his research. According to a statement he issued in 1998:

As I have stated repeatedly in the past whenever this issue has arisen, my use of paid prisoners as research subjects in the 1950s and 1960s was in keeping with this nation’s standard protocol for conducting scientific investigations at that time.

To the best of my knowledge, the result of those experiments advanced our knowledge of the pathogenesis of skin disease, and no long-term harm was done to any person who voluntarily participated in the research program.

Meanwhile, the former inmates argued they had not be made fully aware of the risks. As Jones stated during a protest that same year:

These tests were unfair; they were barbaric…We were lied to; we were used and were exploited. We were human guinea pigs.

There have also been those who have argued that by their status as incarcerated individuals that prisoners cannot make a fully informed consent because, as people legally deprived of certain rights, they are subject to institutional coercion (there are studies arguing for or against inmate medical volunteers as being coerced). The issue a thorny legal and ethical discussion.

The debate over informed consent return to prominence in the the late 1990s when Allen Hornblum, a professor of criminal justice at Temple University, published Acres of Skin, a detailed history of the experiments. Hornblum’s first encounter with the Holmesburg inmates was while teaching an adult literacy course at the prison in the early 1970s. Naming his book after Kligman’s infamous comments, Hornblum documented the experiments through prison records, declassified government papers, and inmate accounts. The shocking accounts depicted in Acres of Skin triggered renewed outrage. In 1998, Jones and several other former inmates staged protests outside of the University of Pennsylvania Hospital. On October 29, 2003, ten former Holmesburg inmates, along with Jones armed with a megaphone, staged a protest on 22nd Street, just outside the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, while Kligman accepted his Distinguished Achievement Award.

Protests led to legal action. On October 17, 2000, nearly three hundred former inmates filed suit against Kligman, the University of Pennsylvania, Dow Chemical, Johnson & Johnson, Ivy Research Laboratories, and the City of Philadelphia, citing mistreatment, exploitation, and lack of disclosure over the severity of the tests. Some argued they had suffered long-term illnesses as a result of the experiments. The suit demanded financial compensation and free medical care to any inmates who had served as test subjects. However, in 2002 a federal court ruled the statute of limitations had passed and dismissed the case.

The question of whether incarcerated individuals should be used as test subjects in medical experiments has been a subject of intense debate. Regardless of where one stands on the issue, the Holmesburg prison experiments have become a textbook case addressing ethics and informed consent in medical testing and shaped how we view the issue of medical research on prisoners today.

Until next time, catch you on the strange side.