Hello, fellow historio-medico aficionados, and welcome again to another installment of CEPI Curiosities, a monthly foray into the interesting and unusual of medical history. This time around, we are celebrating two milestones. For one thing, it is the first CEPI Curiosities of 2017. It also happens to be the one-year anniversary of this now staple of the CEPI Blog. Over the course of twelve months, it has been my pleasure to let you in on the inside stories of such topics as measuring faces for moral character, electrocuting faces for scientific research, stealing bodies for research, manufacturing bodies for profit, reanimating the dead using root vegetables, and the whereabouts of the skull of one of history’s greatest musicians. This is to say nothing of guest articles from our Karabots Junior Fellows on the difference between venom and poison, the unfortunate life of Harry Eastlack, Chevalier Jackson’s swallowed objects, and the exploits of Chang and Eng Bunker.

For our one-year anniversary, I felt it necessary and proper to go back to our roots: Presidential weirdness. If you recall our first episode, we covered the controversy surrounding the death of Zachary Taylor, which led to his body being exhumed in 1991 and tested for arsenic poisoning. Since today is inauguration day, allow me to shed light on what has to be one of the most unusual inauguration stories: the death of William Henry Harrison.

Harrison is mostly known as a historical footnote these days, known primarily for holding the shortest tenure as president (32 days). Born on February 9, 1773, to a wealthy Virginia family, he went on to serve for twelve years as Governor of Indiana Territory where he gained popular distinction with an armed clash with Native American confederations at the Battle of Tippecanoe (November 7, 1811). He went on to serve in the US House of Representatives and the US Senate and earned the 1836 Whig nomination for president, losing to Democrat Martin Van Buren (electoral count 170-73).

He faced Van Buren again in a Presidential rematch four years later, this time defeating the incumbent (electoral college count 234-60) thanks in no small part to the Whig’s campaign strategies. Advocates for Harrison painted him as a war hero under the catchy slogan of “Tippecanoe and Tyler, Too.” Democrats criticized Harrison’s advanced age (67) and argued he should be put to pasture, not given America’s highest office; Democratic writer John de Ziska commented about Harrison, “Give him a barrel of hard cider, and settle a pension on him…he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin by the side of the fire and study moral philosophy!” The Whigs, in a move that should be familiar to modern audiences, spun the attack into a focal point of their campaign, casting Harrison, despite his aristocratic background, as a common salt-of-the-earth man who could connect to lower class and rural white voters (the campaign came to be known as the “Log Cabin Campaign”).

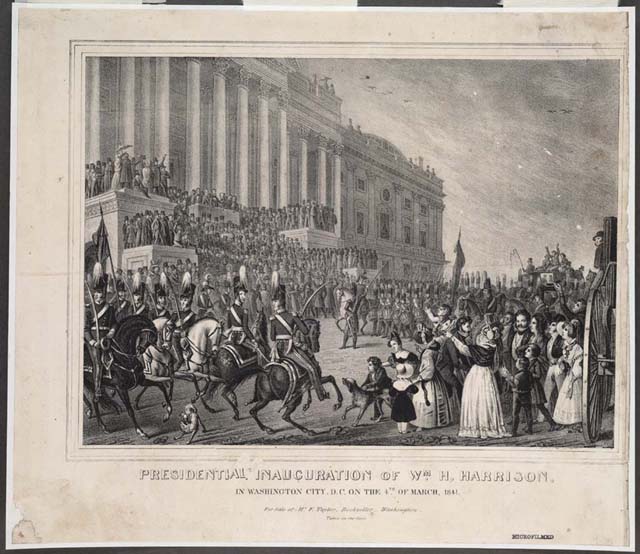

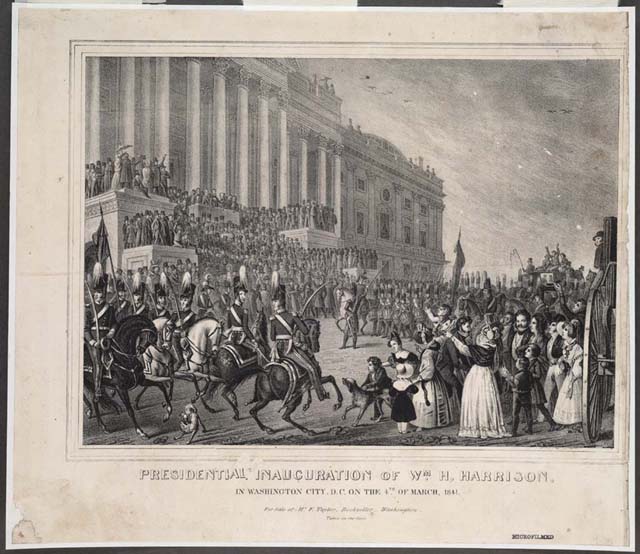

Harrison was sworn in as America’s ninth President on March 4, 1841 (US Presidents originally received the oath of office on March 4, until the passage of the Twentieth Amendment in 1933, which moved it to the current day of January 20). He proceeded to deliver a verbose, rambling, two-hour (8445 word) inaugural address, a speech that remains to this day as the longest inaugural address in Presidential history. Despite it being a cold, rainy day in March, Harrison refused to dress for the weather, foregoing hat, coat, and gloves, as he dispensed long paragraph after paragraph on the historic evolution of representative democracy and the basic duties of the government.

Source: Library of Congress

Roughly three weeks after his inauguration, Harrison began to feel unwell. On March 26, he called upon Dr. Thomas Miller, his personal physician, complaining of fatigue and dyspepsia. Initially, Miller prescribed rest; however, Harrison’s symptoms persisted and he began to experience chills, constipation, and severe pain followed by a heavy cough. Miller prescribed numerous remedies, including laxatives, enemas, and applications of mustard plaster to his stomach (a common 19th century treatment for numerous ailments, including pneumonia); he later blistered the President’s skin (to balance out his humours) and gave Harrison laudanum to relieve pain (a brief report of Miller’s treatment can be read here). Despite initial signs of improvement, his conditioned worsened over the course of the week; on April 3, 1841, at 8:45 PM, President Harrison succumbed to his illness, dying a mere thirty-two days after taking the oath of office. His death gave him the dubious distinction as the first US President to die in office (his death triggered a Constitutional crisis over how succession would work in the event of a President’s death, but that’s for another article).

Most historical accounts cite pneumonia as Harrison’s cause of death, laying the blame on Harrison’s advanced age and long inaugural speech in the cold without proper winter wear as the instruments of his demise.

However, recent scholarship has placed the pneumonia diagnosis into question. To understand why, you need to briefly understand how pneumonia affects the body. According to the American Lung Association, pneumonia is a respiratory disease caused by numerous factors (viruses, bacteria, fungal infection, complications from another respiratory illness such as influenza); whatever variety of the disease, when it infects the lungs, pneumonia causes air sacks called alveoli to fill up with fluid. This fluid buildup can restrict the amount of oxygen the lungs take in when a person breathes; that lack of oxygen can cause cell damage that can eventually be fatal. People of any age can contract pneumonia but it is especially serious when the patient is very young or very old. Symptoms include a heavy cough, fatigue, fever, chills, and difficulty breathing.

Some of Harrison’s symptoms, namely the chills, pain, and heavy cough may point to pneumonia. His advanced age would have made him more susceptible to infection and complications. Pneumonia’s incubation period (the period between infection and when symptoms begin to manifest) is between 1-4 weeks depending on the strain, so it is plausible he could have contracted it during his speech; remember, he reported symptoms to Dr. Miller on March 26 and it isn’t clear how long he was ill before that. However, pneumonia is a respiratory illness (affecting only the lungs) and would not adequately explain his gastrointestinal distress. Recent scientific studies have suggested cold weather may help contribute to illness; however, a person ultimately catches pneumonia from exposure to an infected person, and Harrison’s choice to forego gloves and coat might make him more susceptible to hypothermia (depending on how cold it actually was, and there is some debate over the actual weather conditions in DC on March 4, 1841) rather than pneumonia. Even Dr. Miller himself was reticent to conclude that pneumonia was ultimately what did in President Harrison. In a report in the 1841 edition of Medical Examiner, Miller expressed his doubts with his own diagnosis:

“The disease was not viewed as a case of pure pneumonia; but as this was the most palpable affection, the term pneumonia afforded a succinct and intelligible answer to the innumerable questions as to the nature of the attack.” (Thomas Miller, The Case of the Late William Henry Harrison, President of the United States, Medical Examiner, Vol. 4 (1841), pp 309-12.)

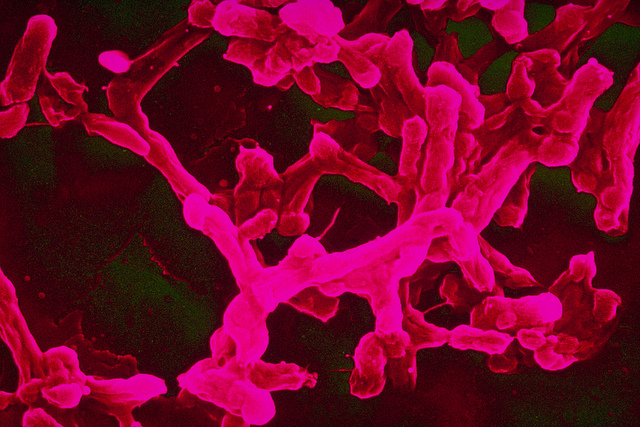

So if it wasn’t pneumonia, what killed William Henry Harrison? A pair of recent scholars have offered an alternative cause of death. Jane McHugh and Philip A. Mackowiak examined Miller’s report and conducted a differential diagnosis based on Harrison’s reported symptoms. In their 2014 report published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, they concluded Harrison’s constipation and abdominal pain pointed toward “enteric fever,” a gastrointestinal illness caused by either salmonella typhi or salmonella paratyphi, better known as typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever, respectively. Both are spread through contact with contaminated food or water and cause high fever, cough, malaise, rash, and diarrhea or constipation.

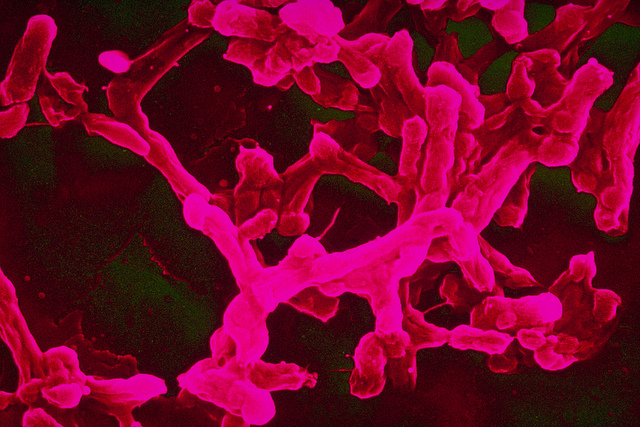

Possible presidential assassin? Image Credit: Sanofi Pasteur, Used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

As to where he contracted it, while Harrison’s speech may not have killed him, his living in the White House very well may have. McHugh and Mackowiak pointed to Washington DC’s lack of an adequate sewer system and the White House’s proximity to a marsh where much of the Nation’s Capital’s human waste accumulated. These conditions combined with general poor sanitation and cleanliness practices in the 1840s created breeding grounds for such diseases as cholera, dysentery, and enteric fever. They further offered these conditions as an explanation for two other Presidential deaths within ten years of Harrison: James K. Polk (cholera, 1849) and our friend Zachary Taylor (cholera morbis, 1850). According to their report:

There is ample reason to conclude that Harrison’s move into the White House placed him at particular risk of contracting enteric fever. In 1841, the nation’s capital had no sewer system (nor, for that matter, did any other American city). Until 1850 sewage from nearby buildings simply flowed into public grounds at a short distance from the White House, where it stagnated and formed a marsh. The White House water supply, which came from springs in the square bounded by 13th, 14th, I, and K streets NW [now known as Franklin Square], was situated below a depository for night soil that was hauled there each day from the city at government expense. This might explain why 3 antebellum US presidents, Harrison, James Polk, and Zachary Taylor, each developed severe gastroenteritis while residing at the White House. (Jane McHugh and Philip A. Mackowiak, “Death in the White House: President William Henry Harrison’s Atypical Pneumonia,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 59 (October 1, 2014), 993-994.)

Following Harrison’s death, Vice President John Tyler ascended to the Presidency, where he was nearly killed in a cannon explosion in 1844. As we’ve already covered, Harrison’s son–John Scott Harrison–was stolen by resurrectionists and sold to an Ohio medical college after his death.

Until next time, catch you on the strange side!