Hello, fellow medico historians specializing in weirdness. Kevin again for another installment of CEPI Curiosities. I seem to have fallen into a rut of stories of mishandled corpses, as I have focused on an allegedly murdered President, a Presidential son/father son who became a medical specimen, and a fake Persian mummy. I had planned to go in a different direction this time around until I came across this recent story by The Guardian reporting that William Shakespeare himself may have been a victim of some cemeterial shenanigans.

As part of a documentary on Shakespeare set to premiere in the UK this weekend, a team conducted an archaeological examination of William Shakespeare’s grave at the Holy Trinity Church at Stratford-Upon-Avon. Their analysis led them to the conclusion that the famous playwright’s skull was no longer with the rest of his remains. This confirmed a long-standing rumor dating back to the 19th century that Shakespeare’s skull had been taken by graverobbers in 1794.

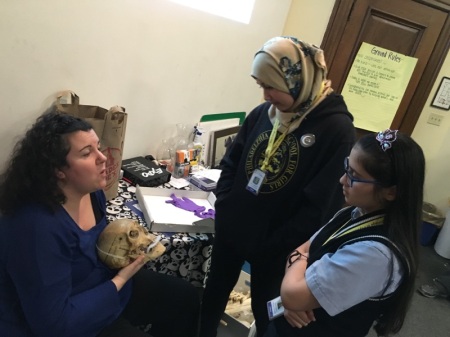

This shocking revelation of the possibly-headless Bard, whose grave site famously curses anyone for moving his bones, reminded me of a similar story of a famous artist whose skull turned missing that involved one of the Mütter Museum’s most famous scientists: Joseph Hyrtl. Hyrtl was a Viennese anatomist who made it his life’s work to disprove phrenology, the belief that the physical dimensions of the skull correlated with personality. To that end, Hyrtl collected and measured hundreds of European skulls. He concluded that the vast disparity in dimensions of European skulls disproved any common connections to personality. His work also disproved the inherent intellectual superiority of Caucasians over other races. Phrenology was commonly used as evidence to reinforce scientific racism, as evidenced by famous phrenologists such as Samuel George Morton of the Academy of Natural Sciences (whose own collection of skulls can be viewed on display at the nearby Penn Museum). In 1874, Hyrtl sold his collection of 139 skulls to the Museum, many of which you can view on display today.

Among the skulls that came into Hyrtl’s possession, rumor has it that one curious cranium belonged to none other than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The legendary Austrian composer and musician died in poverty at the age of 35 and was buried in an unmarked grave in a Viennese common cemetery in 1791. Bodysnatchers allegedly removed his skull, which eventually came into the possession of Joseph’s brother Jacob, who willed it to his brother following his death in 1868.

However, before you rush to the Mütter Museum with your camera and your powdered wig, the alleged Mozart skull was not part of the collection Hyrtl sold to the College of Physicians. Rather, Hyrtl willed the skull to the Austrian city of Salzburg in the early 1890s. Following his death in 1894, the skull reportedly changed hands and eventually appeared in the collection of the International Mozarteum Foundation in Salzburg (read a detailed account here and here), where it remains to this day (although it is not on display to the public).

Whether the skull really belonged to Mozart has never been definitively proven. The Mozarteum skull has been subjected to numerous forensic tests over the years, including DNA analysis and two separate facial reconstructions. These tests revealed differing conclusions over its authenticity. There is also some scholarly debate over whether the skull at the Mozartium is the one previously owned by Hyrtl, as there are inconsistencies between Hyrtl’s descriptions and the Mozarteum skull. We may never know whether the skull really was Mozart’s.

In the meantime, be sure to not lose your head and come to the Mütter Museum to check out the Hyrtl Skull Collection and many other specimens from the history of medicine. Until next time!