Image Source: Sheila Nalwoga

From all of us here at the Center for Education and Public Initiatives of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, we wish you all a happy, healthy holiday season!

Image Source: Sheila Nalwoga

From all of us here at the Center for Education and Public Initiatives of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, we wish you all a happy, healthy holiday season!

Greetings and salutations, medico-historico enthusiasts and welcome to the latest installment of CEPI Curiosities, our regular look back at the thought-provoking and downright strange from the history of medicine. Past forays into the medically weird have included 1990s anti-drug PSAs, the famous Siamese Twins (Chang and Eng Bunker), and a physician who collected thousands of swallowed objects.

This month’s iteration is a continuation of our look from last month at physiognomy, the pseudoscience of divining evidence of one’s character by examining the physical dimensions of their face. As I enumerated upon last month, physiognomy, as with phrenology, was next to impossible to measure scientifically and, again as with phrenology, gradually fell out of favor. This time around we are going to take the science of faces from a different direction and examine some interesting, dare I say shocking, facial research. Today, it is my pleasure to introduce you to renowned faceologist (well, technically, French neurologist) Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne.

Duchenne was a pioneer in neurology. He was one of the first in his field to use electricity to study muscular anatomy, also known as myology, and was an early adopter of photography, using the new medium to record his experiments. Among his contributions to the field was his extensive research on the myology of the face, which he first published in his 1862 treatise The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression (TMHFE). One of the legacies of his research is a genuine smile (one where the sides of the mouth curl upward, the cheeks raise, and the eyes form crow’s feet) is known today as a Duchenne smile. A contemporary of the physiognomy movement, Duchenne was politely dismissive of Lavater’s conclusions, in part calling out the Swiss theologian for his silence on facial movement to say nothing of his lack of scientific credentials, writing:

Lavater devoted himself to the study of facial expression at rest, of physiognomy as such. His research was concerned with the difference between the combinations of contours and lines, the profiles and silhouettes that make up the static face. He certainly would not have neglected as much as he did of the study of facial expression in movement, which should serve as the basis for the examination of the physiognomy at rest, had he been either an anatomist or a physiologist or a doctor or even a naturalist. Duchenne The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression 4.

Rather than study the face to measure the temperament of the human soul, Duchenne focused on mapping the functions of human facial muscles to determine what specific muscles a person used to convey different expressions. This is where the mention of Duchenne’s dual interest in electricity and photography become important, because Duchenne drew his conclusions by shocking patients’ faces with electricity and photographing the results. Even Duchenne himself was aware his methodology might come as…er…shocking to his contemporaries, musing in the early pages of TMHFE: “No one thought that the study of myology could benefit from gross experiments by a physician who provoked convulsions on the faces of his tortured subjects using electrical currents” (Duchenne 10).

Between 1852 and 1856, Duchenne conducted his experiments on a series of live human subjects, including a young man, a nine-year-old girl, and an elderly woman. However, he performed the bulk of his tests on an elderly man with localized facial paralysis that left him with an inability to feel pain. Duchenne described him as an ideal candidate for this sort of experiment because “I could stimulate his individual muscles with as much precision, and accuracy as if I were working with a still irritable [responsive to stimuli] cadaver” (43). He had each subject convey a facial expression displaying one of several emotions, which he listed as attention, reflection, aggression, pain, joy, kindness, scorn, lasciviousness, sadness, crying, sniveling, surprise, and astonishment. Duchenne then recreated the expressions by subjecting parts of the patients’ faces to localized electric shocks. In both cases he photographed their visages, publishing 73 photographic plates in TMHFE.

What I find especially interesting about Duchenne’s work, aside from the whole zapping people’s faces part, is his photographs provide a contrast to what one typically expects from historic photography. Long exposure times and the novelty and highly specialized nature of photographic technology led many 19th century portraits to take on a serious, or downright somber, tone. The Civil War photography of Mathew Brady offers an example of the gravity of 19th century portraits and provides the glimpse most modern observers think about when they think of the 1800s.

1864 Portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Matthew Brady; Source: National Archives and Records Administration

By contrast, in Duchenne’s imagery, we see people in various stages of joy, fright, sarcasm, and downright silliness; something people tend to associate with more modern images.

To bring Duchenne into the present day, his work recently gained some popular attention during the 2016 US Presidential Election. Richard E. Cytowic, a professor of neurology at George Washington University, observed during the Republican primaries that Texas Senator and Presidential hopeful Ted Cruz stood at a disadvantage among voters because he lacked a Duchenne smile.

Now, while physiognomy has been disproven, there is a natural response to attempt to ascertain a person’s character by looking at them. It is a practice frequently seen in visual-based fiction, such as movies, comic books, and cartoons, where facial characteristics are used as a visual shorthand for viewers (think about the last TV show or film you watched; were you able to tell who were the “good guys” and “bad guys” by simply looking at them). The same, in this particular case, goes for politics.

And that wraps up our look at physiognomy and the science of faces. Until next time, catch you on the strange side!

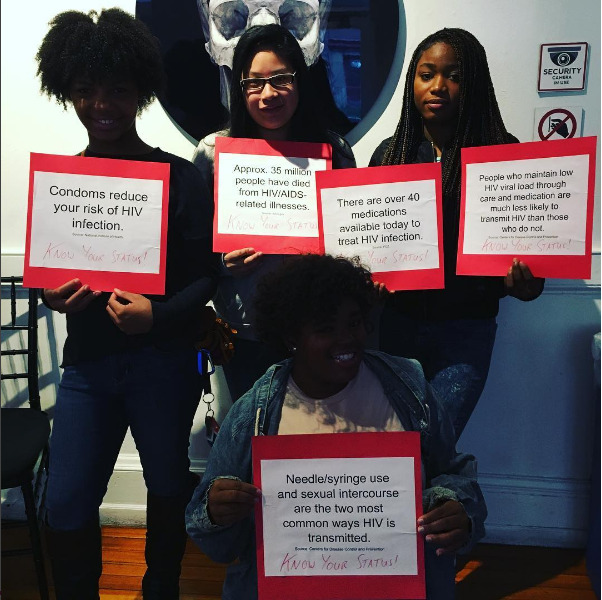

On December 3, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia observed World AIDS Day 2016 with a day-long event to promote HIV/AIDS awareness, dispel the stigma and misconceptions associated with the disease, and encourage people to get tested. Visitors to the Mütter Museum received free admission in exchange for an HIV test (they involve a simple blood sample and test results are known in 60 seconds, a small price to pay for a day at the Museum and certainty over one’s status). It was a large undertaking; fortunately we had on hand a dedicated group of CEPI youth to help out.

Representing the Karabots Junior Fellows Program, the Teva Pharmaceuticals Internship Program, and the Out4STEM Program, our intrepid volunteers were instrumental in logistics, education, and promotion. They directed visitors who came to get tested to make sure the process was as quick and easy as possible. They encouraged people to pose with images of HIV/AIDS-related facts and share them on social media. They also helped educate the public with small health-related lessons, including a lesson on bone pathology using models of human skulls. Overall they helped make for a successful event wherein we tested eighty-five people!

As part of their year-long study of the medical and social construction of the body, the students of the Karabots Junior Fellows Program are preparing to develop their own exhibit. To help them better prepare and to understand how museums use human and animal specimens to teach the public, they recently visited the Academy of Natural Sciences to explore their animal displays. Founded in 1812, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia seeks to educate the public in subjects related to natural history. They feature an impressive collection of flora and fauna specimens, including prehistoric skeletons, a live butterfly room, and taxidermy displays of various species that recreate them in their natural habitats (known as “habitat dioramas”). Timshel Purdum, Assistant Vice President for Public Experience, led the Fellows on a tour of the habitat dioramas, explaining the process by which the specimens were acquired, how they were prepared for display, and how the Academy uses them to educate the public. She also presented the students with fascinating inside stories about various dioramas (such as the “Franken-moose,” a moose specimen with the antlers of a different moose attached to them) and images from the site’s copious historical records. Afterwards the explored the museum for themselves.

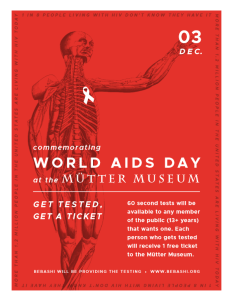

Did you know more than 1.2 million Americans are living with HIV? Did you know that 1 in 8 people living with HIV are not aware they have it? December 1 is World AIDS Day, a day devoted to spreading awareness of HIV/AIDS, offering support to the millions living with the disease, and remembering those who have died from it.

On Saturday, December 3, 2016, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia will be commemorating World AIDS Day with a day-long event to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS, enumerate the facts and myths related to the disease, and encourage everyone to get tested. The College of Physicians of Philadelphia will be offering 60 second tests to any member of the public 13 years or older (testing is provided by Bebashi) with free admission to the Mütter Museum to whomever gets tested. The event will take place from 10 AM-5 PM.